This is the second in a three-part series covering some of the ongoing problems in our current health care system.

Today's focus is on abusive pricing practices in the pharmaceutical industry.

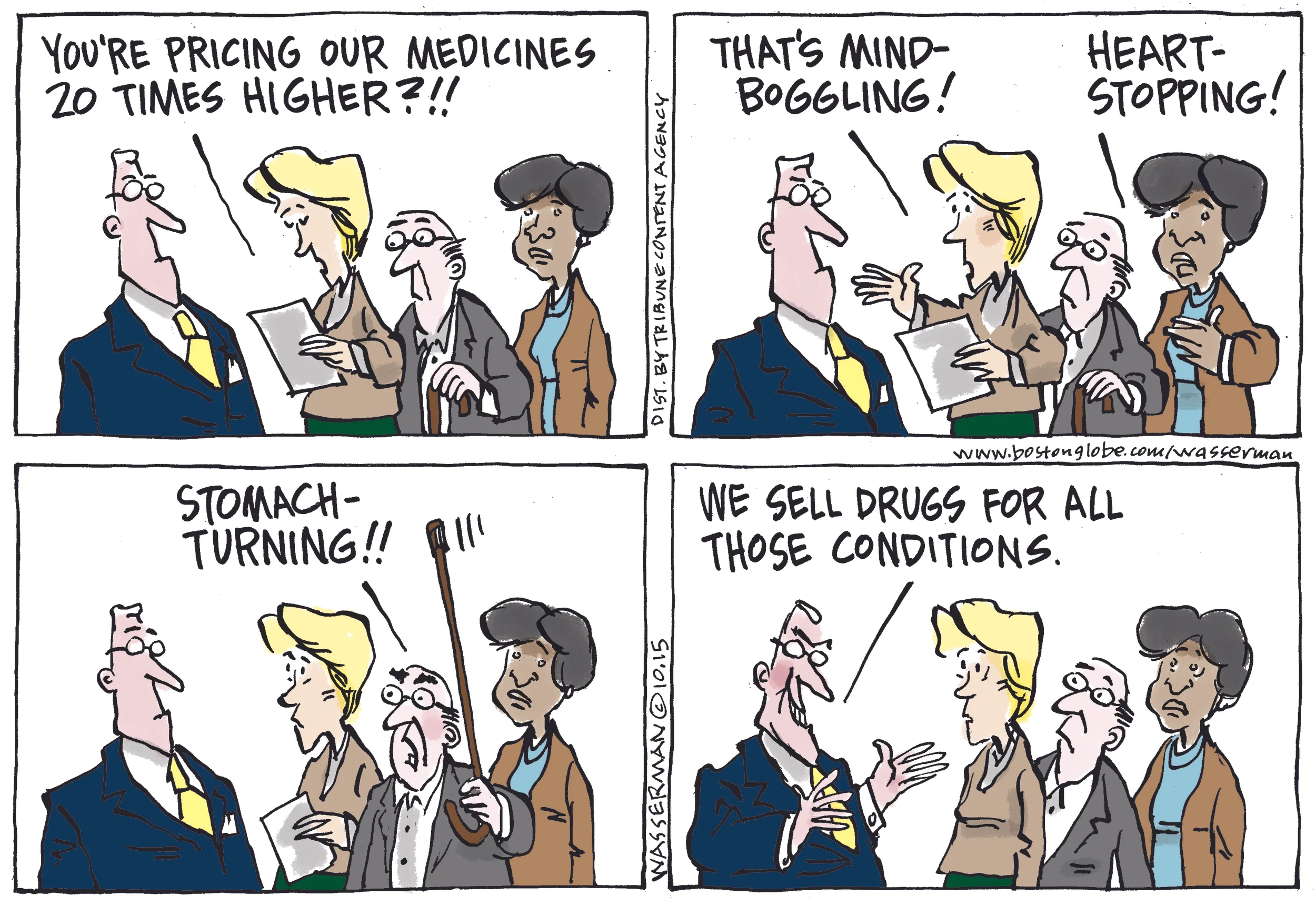

Pharmaceutical Price Gouging

In early October, the press exposed the heinous story of a former hedge fund manager (Martin Shkreli) whose company purchased the marketing rights to Daraprim, a drug most often used by cancer patients, HIV-positive individuals, and others with compromised immune systems. Without any compunction, Shkreli raised the price of the drug by 5,455%--from $13.50 per pill to $750 per pill!

Shkreli's comment to the New York Times: "This isn't the greedy drug company trying to gouge patients, it is us trying to stay in business."

Valeant Pharmaceuticals has also been in the news. The company purchased two heart drugs and immediately raised prices on them by 525% and 212%!

Drug companies argue that these prices are the cost of innovation. But J. Michael Pearson, the head of Valeant, apparently doesn't have much patience for research and development. His business plan was to buy out pharmaceutical companies, "fire most of their scientists and jack up the price of their drugs."

According to the New York Times, Pearson has said he has "a duty to shareholders to wring the maximum profit out of each drug."

These are not isolated examples. As Andrew Pollack of the New York Times points out: "While most of the attention on pharmaceutical prices has been on new drugs for diseases like cancer, hepatitis C and high cholesterol, there is also growing concern about huge price increases on older drugs, some of them generic, that have long been mainstays of treatment."

Reproduced with permission from Dan Wasserman.

Putting the Brakes on Over-the-Top Drug Prices

How do generics fit in?

While the pricing on some generic drugs is being affected by the practices discussed above, generics--and individual pharmaceutical ingredients--can be part of the solution. Imprimus Pharmaceuticals recently announced that it is offering an equivalent to Daraprim at $1 a pill, not $750. How can the company do that? Daraprim is made by compounding two active ingredients: oyrimethamine and leucovroin, both of which have been around for more than half a century.

Mark Baum, founder of Imprimus, points out that "we have had financial types for years now buying up the sole-source generics like they would baseball cards or other collectibles, and then jacking up the price. There's no real innovation." The secret of Imprimus is compounding. If physicians write prescriptions for the individual active ingredients of a drug instead of its generic trade name, the company argues that billions of dollars could be saved over time.

Legal barriers and proposals

In several states, lawmakers are introducing drug price disclosure bills, but even such a mild approach, which does not ensure lower prices, is being opposed by the pharmaceutical industry. What really is needed is for the US government to finally seriously address this outrageous price gouging.

For example, under current federal law, Medicare--one of the largest purchasers of health care in the United States--is prohibited from negotiating drug prices. And, as Andrew Pollack and his fellow New York Times reporter Sabrina Tavernise remind us in a recent article, "the United States, unlike most countries, does not control drug prices, and pharmaceutical manufacturers have relied heavily on steady and sometimes outsize price increases in this country to bolster their revenue and profits."

How Would the Health Security Plan Help?

The New Mexico Health Security Plan is authorized to negotiate prices for pharmaceuticals, as well as other medical equipment and supplies. With over 1.5 million people covered by the Plan, its negotiating power will definitely help to control prices for New Mexico residents.

In addition, the Plan must establish a Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee that will evaluate a drug's "safety, efficacy, and effectiveness" as well as its price. (The Health Security Act, 2015 Senate Bill 262, pp. 20-21, Section 11, Subsections O and P.)

Next up, increasingly restrictive provider networks . . .